The Space Between

Cultivating a sense of balance is one of the hallmarks of a yoga practice — not just physical balance in the sense of standing on one leg or working on an arm balancing pose but also finding a work-life balance, creating a field of emotional stability for yourself and your loved ones, establishing cycles and patterns in your daily life that nurture you and enable you in turn to nurture and support others.

Life can sometimes seem like an endless stream of overlapping and never-ending activities, tasks, and responsibilities — and sometimes it is — but it doesn’t have to be like that all the time. One of the ways to streamline and redesign the flow is to examine the space between.

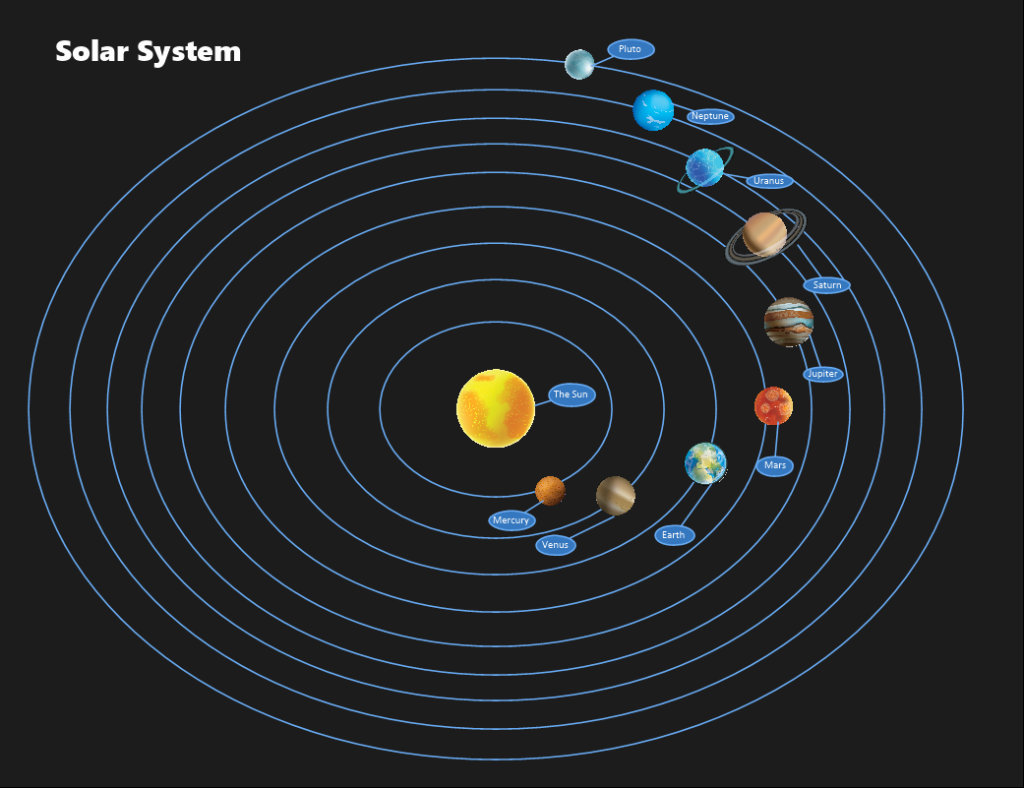

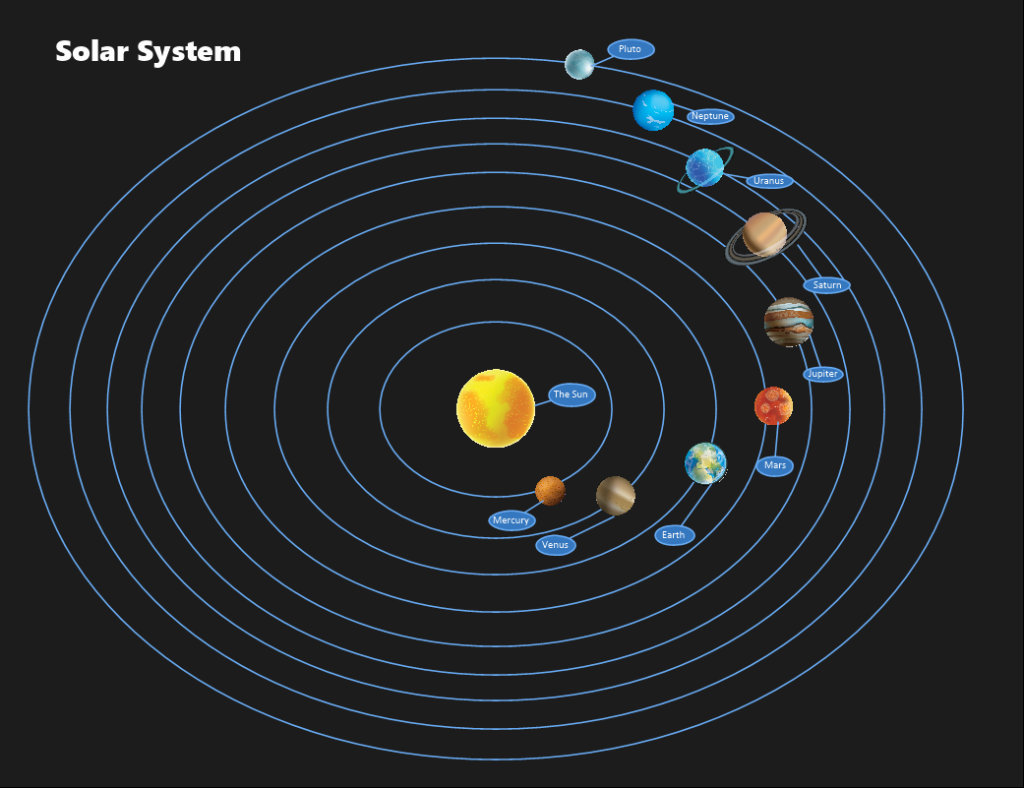

Think about our solar system. You have the sun in the center surrounded by planets and their moons, as well as dwarf planets, asteroids, comets, and meteoroids, all of it swirling around the sun in organized chaos. But the most remarkable thing is how much space there is between the objects. The solar system is mostly space, emptiness, nothingness.

Look at your life and you’ll see something akin to the solar system — a lot of activity and debris that we have to either dodge, deal with, or eliminate. But how?

You could do an inventory of everything you have and do with an eye toward discarding everything that doesn’t bring you joy (a la Marie Kondo). But you’ll end up with a pile of things that need to be dealt with, and instead of seeing individual objects and activities, you might see an impenetrable mass that may be more terrifying and daunting than what you started with.

Take a moment to figuratively spread out all these items, whether physical objects or tasks or obligations. Instead of seeing a confluence of responsibilities, view each as its own entity. Make it more manageable in your mind’s eye. If it’s a task or obligation, determine whether it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. If you deem it as ongoing, can you break it down into subcomponents or tasks that have distinct parameters or borders? Perhaps you have taken on managing an elderly family member’s finances; this may seem like a task that stretches forward in time with no predictable end point. While that is in once sense true, look at the individual points along that continuum: paying bills, for example. One bill, one check. Done. You’ll have to do it again, but each time is a separate event separated by time and can be viewed as less daunting when it’s not a pile of bills to go through and pay.

That’s all fine for tangibles, but what about intangibles? How can we view the jumble of emotions and thoughts we have every day not as a cluster bomb of potential self-destruction but rather as individual micro-events with beginning and ending points?

Sometimes these emotions continue to build and swell and take over our well-being. It’s easy enough to be swept into that vortex. Instead of letting them build and conjoin, try this approach: when a thought or emotion begins to feel overwhelming, stop what you’re doing and step back to see the bigger picture. Ask yourself to identify the source of that thought or emotion (if you can). Is it within you or has it penetrated your internal world from the external world? Is the source something you can control or change? If not, reassure yourself that what you can control is your response to the source. If it is in your control, can you determine a way forward that doesn’t drag along the negative emotions you’ve already experienced?

These actions and approaches are sometimes easier said than done. But what if I told you you could manage, transform, or eliminate the overwhelming elements by approaching them on the most basic, most fundamental level with something that we all do naturally? You’d be on board, right? So here it is: breathe.

You may have to start by reminding yourself to breathe. Sometimes we end up holding our breath when faced with daunting challenges — when we really could benefit from breathing fluidly. So begin paying attention to how you breathe. Try to deepen the breath whenever possible, inhaling down into the belly as much as you can. Deep belly breathing has a calming effect. So, too, does elongating the exhalation.

Try this: breathe in deeply to a slow count of three. Follow that by exhaling to a slow count of four. Next try extending the count, inhaling to a slow count of four, exhaling to a slow count of five. Do this until you feel you’ve reached your sustainable maximum. Calming yourself is the first step toward being able to handle everything you have to do or all the things you’re feeling.

Kumbhaka, or breath retention

Now this is the technique I’m leading you to. It’s simple, it’s effective, it gives a new perspective. What I’m offering is a simplified version of kumbhaka. Once you’ve reached a relatively calm state, you’ll start exploring the space between two breaths.

Inhale and exhale normally. A deeper breath would be helpful, but just breathe. After your exhalation, pause before inhaling again. It might be for one second, or two, or more. As you continue to inhale, exhale, and pause, notice what happens in the space between two breath cycles. You may want to follow one round of kumbhaka with two or three normal breaths.

Now try this variation: After you inhale, retain that sense of full expansive breath before slowly exhaling. It might be for a second or two, or you might be able to retain the inhalation longer. You’re now exploring the space between the two halves of the breath cycle.

Practicing kumbhaka — like all pranayama (breathing ) techniques — helps focus the mind in the present moment, shifting thoughts and concerns to the background and bringing things into perspective.

Another way of viewing Kumbhaka is by thinking of it as a roller coaster. The inhalation is the roller coaster car climbing the steep hill. Then there is that moment when the car crests the rise and feels suspended between ascent and descent. This is followed by the release, the exhalation, the descent of the car from the peak and down the other side. If you’re practicing the retention of the exhalation, think of it as the coasting phase after the car descends from the peak; its momentum carries it along the path without application of force or effort.

By separating the breaths (or the phases of the breath) in kumbhaka, you can begin to build a practice of noticing the space between emotions, thoughts, events, tasks, responsibilties. Maybe even the spaces between days, weeks, months, years. Make your life manageable by breathing. Create space and allow things to flourish in their own time and in their own way. Life may become less stressful and more enjoyable as a result.

Lindel Hart teaches yoga online for PerfectFit Wellness. He lives in Western Massachusetts and teaches at Deerfield Academy, a private residential high school, as well as at Community Yoga and Wellness in Greenfield, MA. Visit his website, Hart Yoga.